Women take an early lead in struggle for teachers’ bargaining rights.

Langley, 1939–40. Forty Langley teachers (mostly women) and led by Connie Jervis took on their school board and other community leaders in their struggle to have an arbitrated salary award implemented. They endured vilification in the local and regional press, were fired, reinstated then demoted. They persisted and won an important victory for all teachers.

BC teachers achieved full bargaining rights (the rights to bargain all terms and conditions of employment and to strike) 25 years ago in 1987, a full 70 years after the formation of the BCTF. The BC teacher quest for full bargaining rights is an interesting and engaging history with many fascinating stories that outline the different steps we took on the way to getting there. The Langley affair is one such story.

After a number of local conflicts including strikes in Victoria (1919) and New Westminster (1921) and years of presentations from the BC Teachers’ Federation, the BC government, in 1937, finally introduced legislation that enshrined in law compulsory arbitration as the dispute resolution for teacher negotiations. This was an important victory for teachers who had been essentially at the total behest of their school board employers. This new legislation did not sit well with some school boards. The Langley School Board chose to disregard this new law. So this is the story of how a courageous group of Langley teachers, mostly women, successfully challenged their school board by insisting on their legal rights and thus the right to arbitration became a reality for BC teachers.

In 1939–40, Langley was very much a rural school district; most residents were farmers. Canada had declared war on Nazi Germany in September of 1939 and, as elsewhere across the country, young men from Langley volunteered for war duty in Europe. There were about 50 teachers in Langley School District and most of them (but not all) were members of the Langley Teachers’ Association and the BC Teachers’ Federation. The annual salary of an elementary teacher at this time was about $780 and for a senior secondary teacher $1,100. There was no common or agreed to salary grid and women were paid less than men for the same work. The average class size was 45 with some classes in the high 50s. When women teachers married, they were asked to resign. School districts did not have superintendents so school boards had a very “hands on” approach to running the school district.

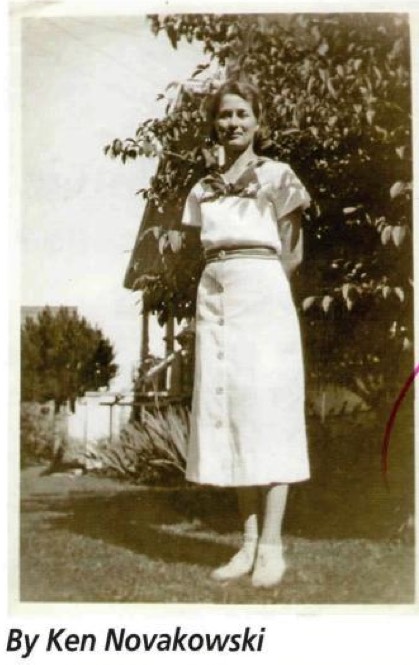

Connie Jervis was the 24-year-old president of the Langley Teachers’ Association in 1939-40. She proved to be exactly the type of leader the Langley teachers needed to see them through the difficult times they would encounter with their school board. She was thoughtful, intelligent, well spoken and most of all persistent and courageous.

Prior to 1939, Langley teachers did not present a collective position on salaries to their school board. As was the common practice in many school districts, the Langley School Board unilaterally set teacher salaries. In 1939, Connie Jervis helped organize a meeting of members of the Langley Teachers’ Association at the home of Roy Mountain who was salary chair for the teacher group. The teacher meeting put together a salary case and prepared to go forward and present it to their school board. BCTF president John Sutherland attended the meeting to indicate the support of the BCTF for this initiative.

The school board refused to agree to any increase in teacher salaries. Fully aware of the new arbitration legislation passed in 1937, Connie Jervis and the Langley teachers requested that the matter be referred to binding arbitration and it was. The school board, however, refused to co-operate and would not attend the arbitration hearing so the provincial government named a person to represent the Langley Board on the panel. The panel went on to rule in favour of the teachers. The school board, through the local media, the Langley Advance, attacked the teachers for daring to invoke compulsory arbitration. In the January 25, 1940, issue of the Langley Advance, school board chairman, J.W. Berry, referred to compulsory arbitration as “the pistol to the head” approach. Teachers were called unpatriotic for wanting a salary increase. The school board refused to pay the arbitrated award and had the full support of the municipal council for their position.

In the spring of 1940, the teachers took the school board to New Westminster County Court to enforce their arbitration award. Using the salary case of teacher Ronald Nordman, Judge David Whiteside ruled that the board had to pay him $880, the arbitrated award and $42 greater than his previous salary of $838. As a result of the Nordham court victory, 40 Langley teachers were to be paid an aggregate sum of $2,500 over their 1939 salaries. The board reacted badly. In the April 4 issue of the Langley Advance, board chairman Berry stated that any teacher requesting the arbitration award would be declared “obnoxious by the taxpayers of the municipality who they are serving and their resignations would be forthwith asked for.” No teachers resigned.

On June 20, 1940, the Langley School Board fired Connie Jervis and 13 other teachers. Ten of the 14 were women. They immediately appealed their dismissal to the Board of Reference, a provincial body consisting of the representative of the BCTF, the BC School Trustees’ Association, and a third person chosen from the legal profession and appointed by the Chief Justice of the province. The Board of Reference ruled that no legal cause existed for the dismissals and its findings were confirmed by the Council of Public Instruction (the equivalent of the Ministry of Education) which ordered the reinstatement of the dismissed teachers in the positions held by them prior to their unjustified dismissal.

But still the school board persisted. When teacher assignments were posted in the Langley Advance over the summer, Connie Jervis, Roy Mountain, and three other women teachers had been demoted by the school board and sent to remote and outlying schools. It should be noted that most people at this time did not have cars and travel within the district was difficult.

On school opening day in September 1940, Connie Jervis and the other demoted teachers went to the schools and classrooms that they had taught in the previous June and sat at the teachers’ desks. The Vancouver dailies attacked the teachers for this tactic and referred to it as a “sitdown strike.” The chairman of the school board, J.W. Berry, went from school to school ordering the women teachers to go to their new assignments.

All this was done by the school board in open defiance of direct instructions from the highest educational authority in the province. The aggrieved teachers again appealed to the Council of Public Instruction.

The Council of Public Instruction ousted the Langley board and appointed in its place a public trustee. The demoted teachers returned to their “June” teaching positions and Langley teachers were finally paid their arbitrated award, but not without more public vilification. The September issue of the Langley Advance in an unusually large (for the time) headline declared “Langley Feels the Unwarranted Blow of Gov’t. Dictatorship” and further declared the event to be the “most serious in Langley’s history.” One can only imagine how isolated and intimidated Jervis and the other teachers must have felt.

So what are we to take away from our knowledge of this experience in our history. Several things:

- Women have long played a leadership role in our Federation. Connie Jervis and her women colleagues were a fine example. Connie Jervis’s courage in taking the actions she did is exemplified by a recent statement made by her daughter, Peggy McLay, a current Langley teacher who rightly said: “She bravely took on the pillars of the community with fierce opposition and little to back her up.” It was not an easy struggle.

- Compulsory arbitration for teachers was not further challenged by school boards after the Langley affair. The Langley affair clearly demonstrated that school boards were subject to the laws of the land.

- Local actions do have a provincial impact. The actions of Langley teachers helped entrench a right that allowed all BC teachers to improve their economic status overall.

- Throughout the whole affair teachers had each other and they did have the BCTF. Their strong leadership and their unity were keys to their ultimate victory.

Teacher Newsmagazine

Volume 24, Number 5, March 2012

1939–40: The Langley Affair

by Ken Novakowski (retired teacher from Langley, former BCTF executive director, past BCTF president, currently on the board of the Labour Heritage Centre)